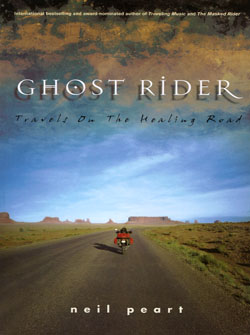

Neil Peart – “Ghost Rider: Travels On The Healing Road”

As I’ve said previously, I’ve felt that Alex Lifeson is “The McCoy” of Rush (the passionate one), whereas Geddy Lee is “The Spock” of Rush (the logical one). To this end, I feel Neil Peart is “The Kirk”, which is considered to be the mixture of the two. Neil is one of the most talented drummers in rock music, and his drum solos are considered legend. If you looked at his face while he was performing them though, you’d think he was doing his taxes with how calm he looks. Also, while Neil has been considered the quiet intellectual of Rush (preferring to keep to himself and not do many interviews), as the band’s lyricist he provides their emotional core. Neil may have been the last member of the band to join, but they’ve undeniably achieved the most with Neil and he is perhaps the heart of the band.

…Which makes it all the more tragic that his heart was broken so completely when his daughter Selena died in a single car accident in 1997, and his wife Jacqueline passed away herself ten months later from terminal cancer. Inconsolable with grief, Neil unofficially retired from Rush and packed up for a motorcycle trip that would last fourteen months, spanning most of North America and Canada. Upon his return to a normal life and his return to Rush, he compiled his journals and letters to friends into the book “Ghost Rider: Travels On The Healing Road”.

This review is going to be a bit different than the others, in that it’s not going to really be a review at all. How can I possibly be empirical or even nit-picky with this kind of subject matter? How can I criticize a book the author wrote to deal with the grief of losing his wife and child? To be blunt, I can’t. What I can say about Neil’s writing style is that it’s very informal and conversational, but still very sharp and erudite. When he’s not writing about his grief, “Ghost Rider” feels more like a straight travelogue, or even a series of anecdotes. He talks at length about each place he goes to, some of the local history, local people, customs, meals he has, friends he visits, funny incidents and encounters. Neil is already no slouch in that department. Having written on an amateur basis for many years, he finally published his own book “The Masked Rider” in 1996, telling stories of a bicycle trip he took through Africa, and would later publish more motorcycle travelogues about stories that happened when he resumed touring with Rush.

To me though, all those things seem incidental to the real subject at hand here: Neil’s grief. Even getting through the beginning of the book was harrowing, as Neil described the long, sleepless night when the local police chief pulled into their driveway and told them that Selena had been killed. And while medically, Jacqueline’s death was from cancer (which is also described in harrowing detail as she breathes her last in a hospital in Barbados), Neil is insistent that it was really from a broken heart, with the unfathomably sad summation of “she just didn’t care”. Even before the cancer diagnosis, her friends and family were keeping an eye on her sleeping pills and making sure she wasn’t alone. From the way he describes it, she didn’t so much “die” as “waste away” in the wake of Selena’s loss, taking out most of her despair on Neil in the meantime (even flat out telling him “Don’t be hurt, but I always knew this would be the one thing I just could not handle”).

As Neil begins his motorcycle trip in earnest (something Jacqueline predicted and suggested he do before her passing), one thing I notice is how much he dissociates from his life before Selena’s death. Watching his old instructional videos on drumming, he remarks he doesn’t even see himself in that guy on tape anymore. He constantly refers to himself as “the fool I used to be” (after lyrics from “Presto”), and quickly has Rush’s bookkeeping staff make him some credit cards with the alias “John Ellwood Taylor” (after his middle name, Jackie and Selena’s last names, and the most common of first names). It seems Neil is constantly inventing new personas; first in John Ellwood Taylor (who he considers a wandering bluesman type), next in “The Ghost Rider”, a name he picks up while writing a postcard to Alex Lifeson and later signs on most of his letters to friends and family.

He wants to be anyone but Neil Peart, father to a deceased child and husband to a deceased wife. He wants to be anyone but “the fool he used to be”. When a state trooper looks at his identification and asks if he used to be a musician, Neil just replies “I used to be a lot of things”.

Moments like these hit Neil the hardest in the beginning, thinking not just back on his loss but also every moment of failure, error, or idiocy. He even starts to contemplate his old idols, like Keith Moon from The Who. Neil used to admire his drumming prowess, but then read a biography that shows how Moon was ultimately unstable, unhappy, wasted his talents, and constantly disappointed those close to him.

Perhaps the worst part is when harmless things would trigger him and he would start crying out of nowhere. Like when he passes an old desert graveyard, or sees grandparents with their grandchildren and realizes “I’ll never be a grumpy old grandpa”, or seeing “Grease” (Selena’s favorite movie) playing on the TV. No matter how prepared he is for it or how far he travels, he can’t escape the memories. He even starts pondering what he’s going to do when he can’t ride anymore. He thinks of Ernest Hemingway, who shot himself after being unable to write a simple reply for an invitation to JFK’s inauguration. If he can’t do what he does best anymore, what else is there?

Neil finally bottoms out about halfway through the book when his best friend Brutus, who he had planned on going riding with, getting arrested for possessing large amounts of a certain “leafy green substance”. He laments how his life has turned into a bad country song. His daughter died, his wife died, his dog was recently put down, his best friend has been sent to jail, and he has an ulcer to boot.

The second half of the book is mostly made up of letters, often to Brutus but also to various friends and family of Neil’s. Part of what I like about his descriptions is how he maintains his connections. He makes it a point to see his friends and enjoy himself. We hear him describe outings with the members of Rush and their staff, with famous friends like Dave Foley (back when he was still on “NewsRadio”) and “South Park” creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker (who were still getting off the ground). Neil slowly starts to learn how to enjoy his life again, and he allows himself the pleasure of people helping him.

“Ghost Rider” doesn’t so much end as it stops, perhaps fittingly enough in Death Valley. Shortly after that, Neil met his future wife (photographer Carrie Nuttall) in Los Angeles, and would marry her a year after that. Another year later, he would return to the fold with Rush and would record “Vapor Trails”. And during that time, Brutus would also be released from prison. John Ellwood Taylor, The Ghost Rider, and The Fool He Used To Be all merge into one new person: the new Neil Peart.

Because it’s so hard to review and criticize, it’s hard to say who “Ghost Rider” would appeal most to. Motocyclists and fans of travel would probably enjoy it, and no doubt hardcore Rush fans would probably enjoy an insight into someone who has been relatively quiet most of his career. Really though, I would legitimately recommend this book to those trying to overcome serious grief or tragedy in their lives.

Neil Peart was forced to confront his pain head on and learn to live his life again (with all the good and bad that entails), lest he waste away like Jackie had. He offers no hard solutions or easy answers though, and really how can you for something so unfathomable like losing your wife and daughter? As cruel and painful as it was, what happened happened, and Neil had to continue on.

I enjoyed reading “Ghost Rider” though. It had me contemplating my own mortality and place in the world many times. Naturally, it made me think of those I had lost in my own life, but those I still had with me as well. No one would have blamed Neil Peart for throwing in the towel after Jackie and Selena’s passing. As a Rush fan though, I’m happy Neil found it in him not just to return to the band, but to return to his life.

Discussion ¬